The Great and Terrible Beast

Benjamin Sachs went and blew himself up.

So opens Paul Auster’s Leviathan. Maybe not in those exact words – actually, most definitely not – but that’s the gist of it. Benjamin Sachs – the narrator’s old friend – had seemingly accidentally blown himself up with a makeshift bomb. The narrator takes it upon himself to chronicle Sachs’ life and outline the events that led him to his death.

Leviathan isn’t really a mystery. Although the question of Sachs’ life could be considered a mysterious hook, the novel isn’t a detective story by any stretch of the imagination. Yet, I’m still tempted to write about it all the same, because I found the book compelling in a lot of ways, and I want to make sure to have it all down before I move on and forget.

I’d read Auster’s New York Trilogy a while back. I admit I don’t remember much of it except for its last story – The Locked Room (because of course) – in which an author takes of the life of his missing friend, publishing his work as his own and effectively replacing him in the man’s own family.

A more recent read of Auster’s I had was Oracle Night. Looking up, I see it’s still on my shelf – wedged between Poirot Investigates and an all-in-one-book collection of five Ellery Queen novels. It’s an odd placement, but, then again, not like I’m the one who put it there. It had been my roommate, who had taken it upon himself to organize the books and comics on my shelf, no doubt annoyed by my own lack of organization. The books I’d read at the time went on the shelf, the ones I still had to read went under the coffee table. I think the number of books on the shelf and those under the coffee table is probably similar at this point.

I digress; Oracle Night was the story of an author recovering from an illness and trying to write a new story. It follows the narrator’s day-to-day and his interactions with the people around him – primarily his wife and his old friend. It also follows his writing process – as he constructs the story of a man who abandons everything – his wife, his name, his career, in search of something he himself doesn’t necessarily understand. All he has with him is a recently-uncovered manuscript by a deceased author – bearing the title of Oracle Night – about a man suffering from seeing visions of the future.

It’s a story-within-a-story-within-a-story kind of deal, but it’s also more than that – Auster’s stores always feel mysterious, but the mystery doesn’t necessarily come from the events themselves but the strangeness of the world we live in. His characters always feel just a little larger than you or me, but real all the same. The story-within-a-story-within-a-story structure in Oracle Night is deliberate, but only on a suggestive front. There is no wild “a-ha” moment where there’s going to be a fourth inner story that reveals to be the contents of the novel. The suggestion is what keeps you tied, though – the anticipation of something like that creeps throughout and helps bring into focus the author’s mental state. When his wife comes home and he doesn’t hear her, is it because he wasn’t paying attention? Or was something else the matter?

Of course, as I said, there’s no crazy meta reveal or anything of the sort. But the feeling of unease works very well – worked for me, at least. In reality, it was ultimately a tool to communicate the deeper themes of connection, love and self-deception – of ignorance that we give ourselves intentionally or unintentionally.

What struck me about Auster was his style. The narration always feels so effective and punchy – he knows how to hook you and how to keep you hooked.

You’ll pick up on some common themes and motifs here. His protagonists are usually writers. His characters typically experience a mental break that forces them to break free from their lives in searching for something more.

Benjamin Sachs of Leviathan is no exception. He’s a writer who primarily focused on writing about the state of America. He’s left-wing, he’s spent jail after refusing to go to Vietnam, he’s angry and – he’s something else, too. Something he himself isn’t sure about.

It’s a character that feels oddly relevant in recent times. His frustration is understated throughout much of the novel, but always present in one way or another.

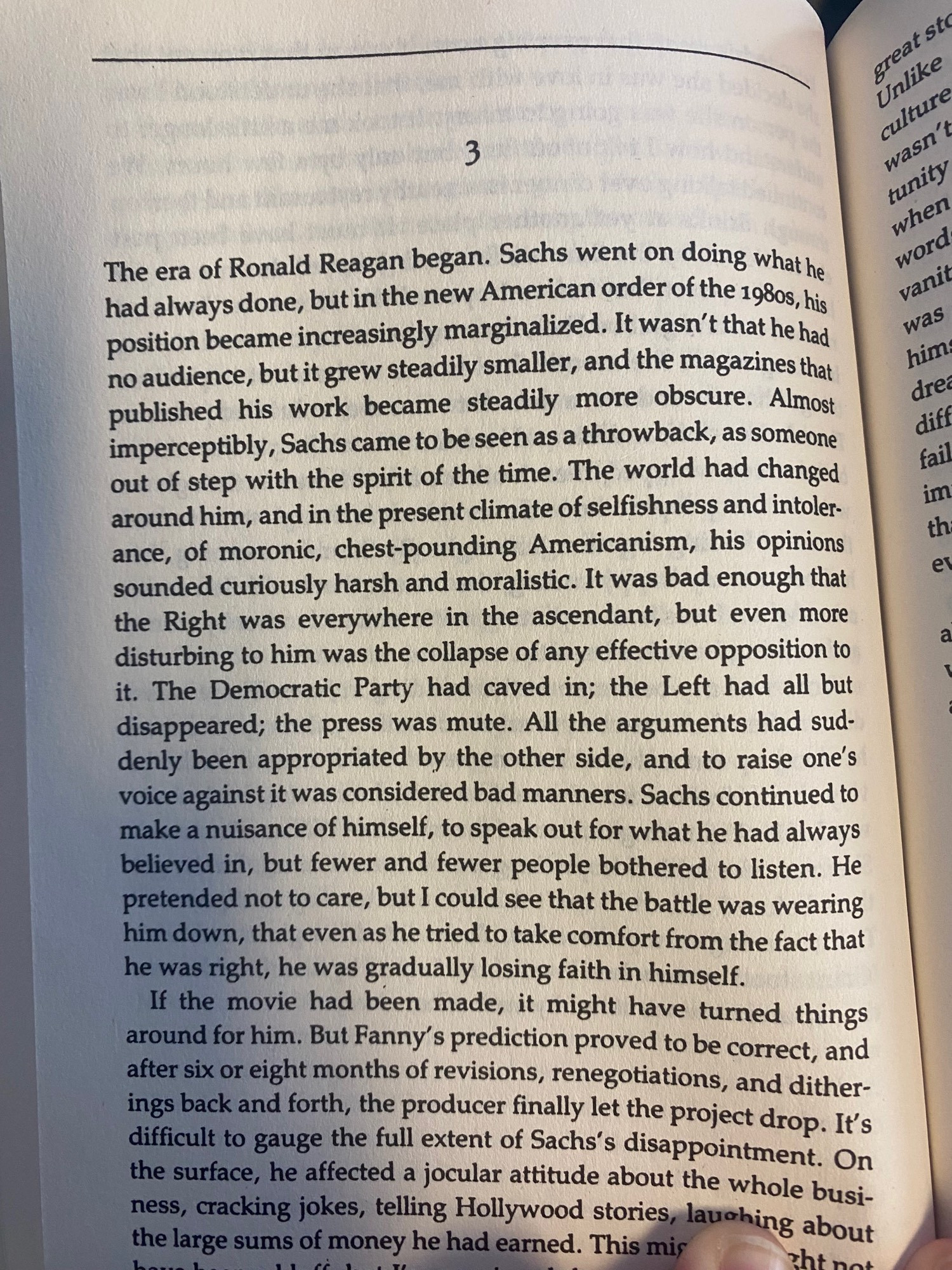

The most notable section for me was this one – in that it showed just how cyclical the world’s history seems to feel:

It’s familiar, isn’t it? A world where a criminal – a fraudster – gets to become president. A world where a tech mogul doing a Nazi salute can’t be called for what it is. A world of sheer and utter complacency from the only people in any political power to do anything to stop the harm to the people they claim to represent. A world where lies go on unchallenged.

It’s strange, isn’t it? Even just describing it, I feel like I’m being preachy. Like I’m overreacting, being too angry, being too dramatic. I guess I, too, am part of the complacency, to an extent. Born with the idea that I am powerless – which, I do believe I am – and ultimately left angry. To not be angry, I must not think. It’s as simple as that.

Those who think too much may end up like Benjamin Sachs.

How depressing. Let’s move on.

After all, Leviathan doesn’t really feel like it’s about American politics. They are a big part of it, don’t get me wrong – especially in Sachs’ life – but Leviathan is ultimately a novel about chance.

Throughout the novel, the narrator emphasizes the power random events had on his and Sachs’ lives. “If I hadn’t met X, then Sachs wouldn’t have met Y. If Z hadn’t happened to me, I would’ve never met my current wife. If W hadn’t picked up that notebook and happened to call up a random number and found out that it was L, then the course of Sachs’ life would’ve likely been different.” Some of the coincidences are truly preposterous – particularly near the end of the book – and very intentionally so.

Auster uses an interesting technique in the narration. Through this kind of “teasing” of “if this hadn’t happened things would’ve been drastically different” and often showing snippets of things to come, there’s a sense of inevitability throughout the entire thing. Which further reinforces the theme of not just chance, but the meaning we assign to it and the meaning we assign to our own actions. It shows how seemingly small events can drastically impact our lives. In part because they can spiral into something much more drastic without us foreseeing it, but also in part due to the ways in which these seemingly insignificant events make us feel. Every interaction has the chance of awakening something in us – something we’ve kept hidden or something we hadn’t even known was there. And other people can’t see or understand it. But they, too, can assign meaning to the ways in which we change before their eyes. Make assumptions. Make mistakes because of those assumptions.

Mistakes which we can blame ourselves for – for a long time.

Product Links (Amazon)