The Freaky Works of Tomoyuki Shirai

I’ve dug too deep. The abyss has stared back.

To be completely honest, I’m not sure if I really want to talk about Tomoyuki Shirai’s works. It’s more that I find myself needing to. Not just because of how upsetting his novels are, not just because of the doors of discussion they open, but because the novels themselves are kind of brilliant. The first point makes the last particularly painful to admit.

The first book of his I read was the The People’s Church Murder Case. I don’t remember how I stumbled across it, but the path it has taken me down since finishing it is something that will stick with me for a long time. When I picked it up, I had no real knowledge of its author or even the novel’s premise. What drew me in was the selling point of a 150 page solution section – about a third of the entire novel.

You’d think that’s a tall order. But the man delivers. And, as I eventually found out, delivers consistently.

In the three novels I’ve read so far, the man seems to revel in long solution sections. The characters build their logic brick by brick, evidence by evidence, Ellery Queen-style. If a solution doesn’t sound convincing, it’s almost certainly intentional, since the writer thrives on creating as many false solutions as possible before finally showing you the truth. Think Death of Jezebel, but every new solution not only proposes a new culprit, but completely reinterprets the entire crime from scratch. And with each solution seeming more likely than the one before it, you’ll almost certainly lose sight of the things that actually matter by the time the final truth is revealed.

As I’ve said – the novels are brilliant. The crimes are well thought-out and well-clued, with not a single scene wasted. These are all, at their heart, puzzle novels. I need you to keep this in mind going forward.

His novels are good. I do not regret reading any of them.

But rest assured, they go out of their way to make you feel otherwise.

The People’s Church Murder Case opens with a mass suicide in the town of Jordentown, a religious commune in Guyana led by pastor and cult leader Jim Jorden. Its inhabitants, most of whom had emigrated from the States in fear of what they perceived was religious prosecution, drink a juice laced in poison. Those unwilling – be they man or child – are either forced to drink the poison or shot upon trying to escape into the surrounding forest.

The novel covers the events leading up to this grand suicide – in which a group of detectives has been hired to live in the commune and determine the legitimacy of the many miracles Jorden and his followers claim he has preformed: from reviving animals, to curing illnesses, to flat-out regrowing people’s missing limbs. If the detectives are satisfied that the miracles are genuine, the man who hired them would agree to sponsor the commune through its ongoing controversies.

Which is why, when the detectives are less than impressed by what they see, Jim Jorden forbids them from leaving.

Beneath the scorching sun and the fly-infested air, the detectives are soon picked off one by one through seemingly miraculous circumstances. Jorden initially denies having a hand in the murders, but concedes that the deaths are likely a form of God’s punishment for their insolence. These murders are particularly ill-timed for him, however, due to an impending visit from an American congressman Leo Ryland.

I’m hoping, from this brief synopsis alone, that you can see what the point of provocation is.

Everything from the title, to the name and location of the commune, to the leader, to the names of some of the people involved, to the visit from the congressman Leo Ryan, to the mass suicide that immediately followed said visit – everything – is intentionally built around the events of the 1978 Jonestown Massacre: in which Jim Jones initiated a mass suicide of his congregation, the Peoples Temple, in a remote commune he’d founded in Guyana.

The murders, essentially, run in parallel to the “fictionalized” version of these real-life events.

The discomfort basically strikes the moment you start reading the book. To call it in poor taste feels like an understatement.

Mystery fiction – fiction in general – is no stranger to placing stories smack-dab in the middle of real-life tragedies or drawing heavy inspiration from them. Jack the Ripper. Titanic. World War 2. Instinctively, we’ve come to generally accept the deviations from the truth in these settings and even enjoyed the creative additions to them. Is it because they feel distant enough from us? If almost everyone involved has passed away, does it mean that we can feel at ease, knowing there’s nobody left to offend? Is it because some of them, like wars, have large enough of a scale to where we can forgive the existence of these, generally inconsequential, events?

You could make the case that fiction is fiction: a safe space to explore different ideas, no matter their setting or premise, with the understanding that it doesn’t, and can’t, change what happened in the real world. After all, Tomoyuki Shirai isn’t saying that this actually happened, nor is he actively trying to take away from the pain and suffering the actual Jim Jones caused.

But, like, surely, as human beings, we can instinctively feel that there’s a noticeable difference between the Titanic and the Charlie Sheen 9/11 movie. We can look at something like One Upon a Time in Hollywood and not consider it as disrespectful, but take issue with The Haunting of Sharon Tate. This isn’t a zero-sum game – it may be fiction, but it still carries a responsibility to approach certain subject matter with a certain degree of respect.

And, brilliant as his solutions might be – I don’t feel Tomoyuki actually did that.

Worse yet – I don’t think he actually tried to do it to begin with.

He builds his puzzles and his core image on genuinely upsetting premises. The People’s Church Murder Case doesn’t upset you through gore or some kind of weird imagery – it does it by knowing full well what it’s doing, and using it to its advantage. That bad taste in your mouth will carry itself through every scene, through every interaction, through every direct invocation of real-life events – and when you get to the end and are forced to acknowledge that it was all used to build a brilliant puzzle plot – it will make you feel bad.

Of course, it’s a trick in its own right. The mystery, at its core, didn’t need any references to Jonestown. It didn’t need a cult leader named Jim Jorden, it didn’t need to be specifically near Georgetown, it didn’t need the visit from the congressman. Yet, by tying the plot so tightly to the setting, it feels like it did. That’s how you lose.

It’s a novel you feel like shouldn’t have been made.

Speaking of–

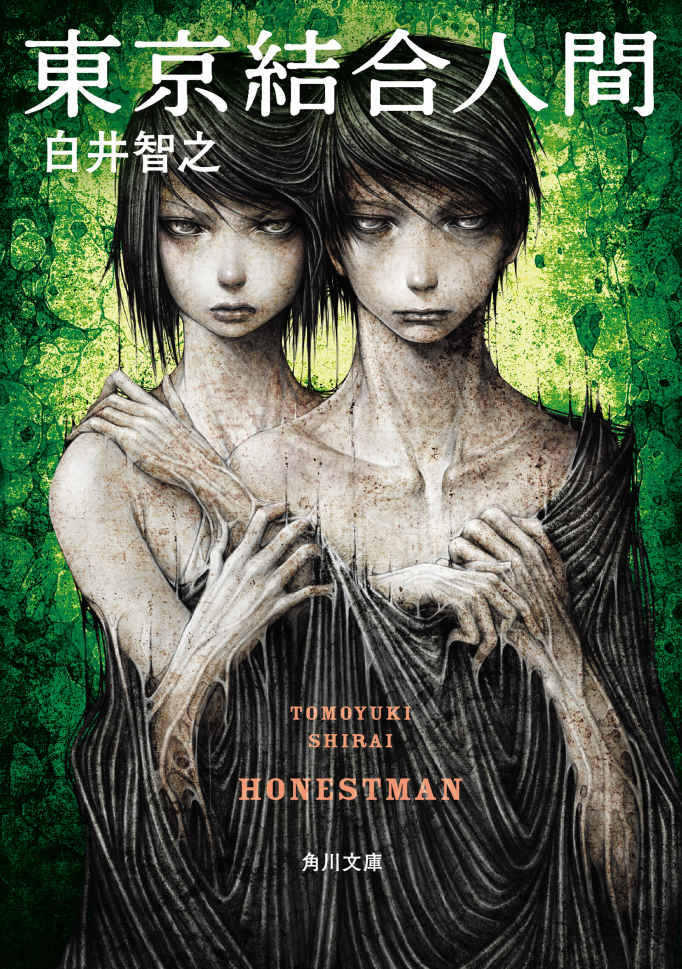

Tomoyuki Shirai’s novel, Tokyo Combined Corpse (AKA HONESTMAN) starts with a woman trying to insert her entire body into a man’s anus as a means of procreation.

¯\(ツ)/¯

The novel takes place in the world where humans don’t procreate through genitalia, and instead procreate by “bonding” with each other: one of the partners enters through another’s anus, leading to the creation of a combined human – a human with four eyes, four arms, four legs, with an expanded brain size and doubled height. In this state, humans are capable of producing babies, which will then go on to reach normal puberty, be attracted to other people, and eventually find an anus to crawl into, forming a new combined human.

The beautiful circle of life.

The humans need to be of opposite sexes. In case of these bondings, there is a pre-defined rule as to which body parts are “inherited” from which partner. There is a rare occurrence in which the donor of the parts is flipped, resulting in a creature physically cannot lie. These combined humans are known as The Honest Men. They have a hard time maintaining work and friendships as a result of their – generally unwanted – honesty.

Following a shipwreck, a group of seven such Honest Men find themselves stranded on an island owned by an elderly painter and his daughter. The island itself has no direct contact with the mainland, and the Honest Men need to wait a week before the next scheduled supply ship shows up and takes them away.

However, on the second day, the painter and his daughter are found brutally murdered. The culprit appears to have taken the weapon from the dormitory the men were sleeping in, and there’s no sign of anyone else on the island. Yet, all seven of the men deny being the killers. What’s going on?

Well, for one, I’ve conveniently left out the events leading up to the shipwreck, which take the first third or so of the novel.

This lengthy prologue follows Rat, Onako and Video – a trio that pimps out underage girls to lonely single men. The book wastes no time establishing that these are truly awful people – and it’s their actions that ultimately lead to the situation on the island.

Some of the scenes in this prologue actually made me queasy – not because of anything that was outwardly shown (in spite of some violence, the book never turns into porn, torture or otherwise), but the sleaziness of it all and the underlying implications of some of the later reveals are genuinely unsettling.

Of course, it’s all in service to the puzzle. The section is littered with information crucial to solving the murders on the island – but you’ll never realize their importance until it’s too late.

It does establish one more important thing right off the bat, though:

Of the seven Honest Men, two are not actually Honest Men.

You may think this completely ruins the mystery. After all, you know this before any of the murders even happen. Yet, the mystery on the island is plotted so tightly that it turns it into a puzzle. You’re never in a position where you can easily just assign two people as liars and call it a day: the mystery still prevails. As I explained in the beginning, all of the reasoning is built on evidence, and there’s a lot of different theories the characters manage to construct in the last stretch.

The book will probably haunt me for a long time.

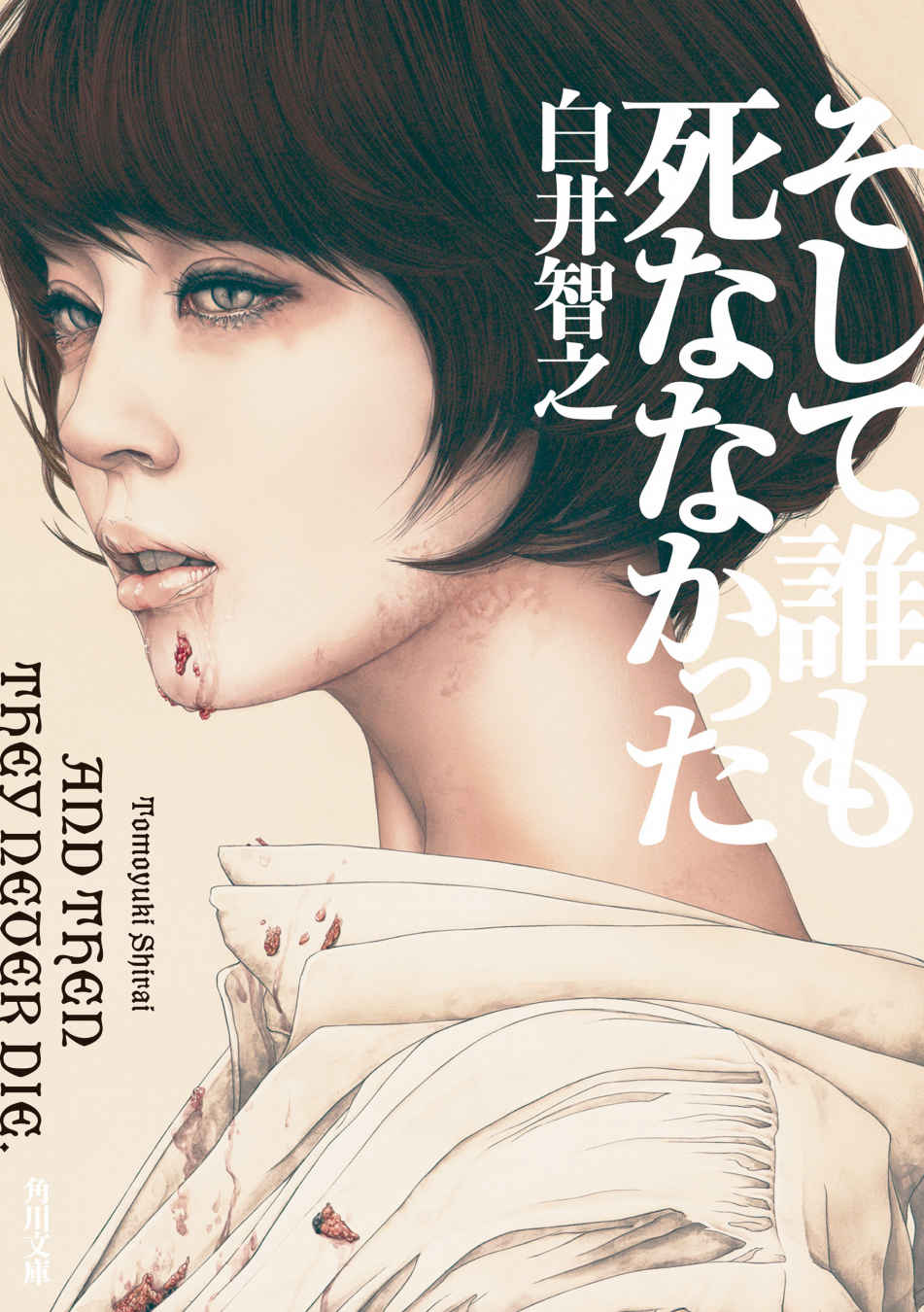

Honestly, everything I’ve just gone through almost makes And Then They Never Die feel tame, even though it’s probably the most brutal in terms of deaths in comparison to the previous two.

Of course, regarding the events taking place on the island as “deaths” doesn’t seem fair. After all, the title is pretty clear: nobody actually died.

…Right?

Well, the setting of this novel follows a group of mystery writers who were invited to the island of a famous masked writer. Realizing that their host is nowhere to be found and finding that the boat they arrived on doesn’t actually have enough fuel to get back to the mainland, they decide to do the only thing they can: nothing. They divide the rooms amongst themselves and spend the night.

By morning, they are all dead.

Except, uh, they’re not.

They most certainly die – in pretty horrific ways.

Yet, one by one, they all return to life, their faculties intact.

The novel follows them as they try to figure out what happened. Who called them to the island? Why did they die? Why did they come back to life? Who is the killer? How did they do it?

In spite of – again – pretty brutal murders, the fact that nobody actually dies gives the novel a bizarrely easygoing feel. It’s a neat little puzzle with some fairly amusing false solutions. The explanation as to why the incident happened is ridiculous, but by the time you see it, you’ll have already gotten accustomed to the book’s weird vibe to not question it too much.

There’s still a sense of unease to all of this – it wouldn’t be a Tomoyuki Shirai book if it wasn’t a little bit gross, I suppose – but it’s definitely nowhere near as bad as the previous two books. The sense of darkness isn’t permeating – I’d say it’s actually actively trying to be funny at times.

But then you remember some of the character backstories and you start to wonder how appropriate the inclusion of humor is supposed to be, and you’re right back playing into the writer’s hand.

That’s the worst part of it. As flat-out uncomfortable as these books make me feel, I’m always at the mercy of the undeniable genius behind them. This is someone that understands the genre, who knows how to create a plot, who can squeeze the most out of his messed up settings and make it work.

In the long run, this all probably says more about me than about the writer. The fact that I kept looking for more after reading The People’s Church Murders in spite of the mixed feelings for it – and the fact that I didn’t give up on Combined Human from the first third alone – probably speaks to my own obsession with the genre.

The abyss is still staring.

The shovel feels restless.

But I’ve dug too deep.

Maybe I’ll wait a bit before I do manage to ruin it for myself.

Product Links (Amazon)