Writing about Writing on Writing through Writing

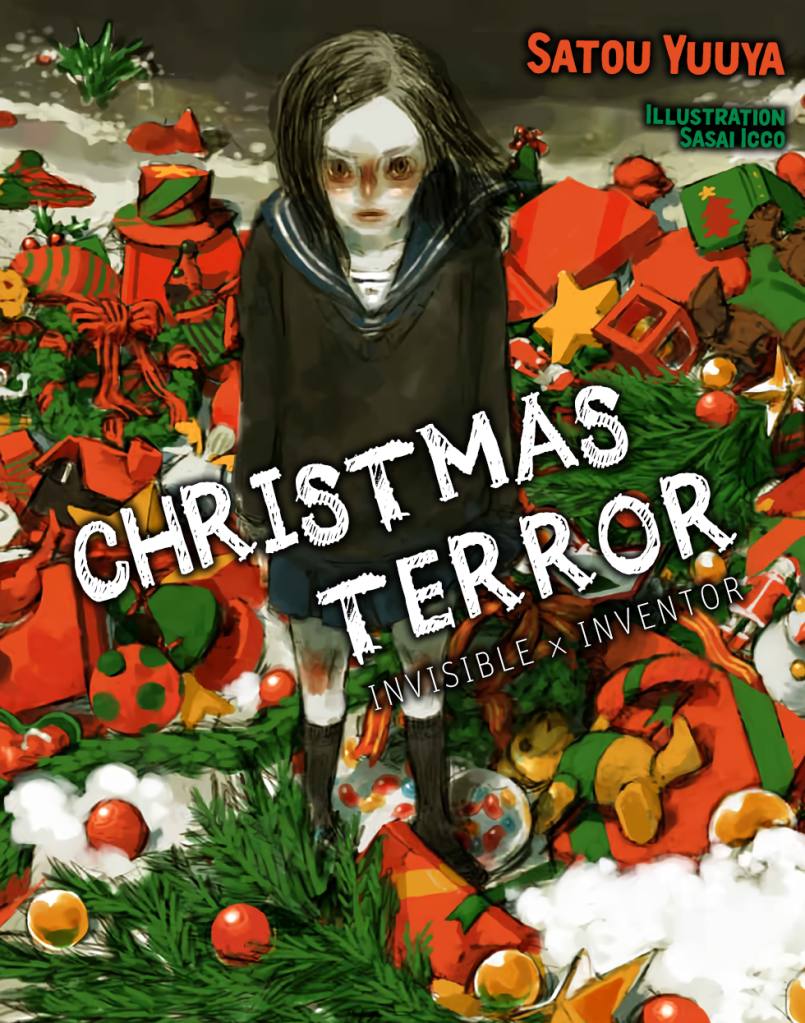

My back is starting to hurt. Not hurt hurt, it’s more like a slight discomfort. Not a big deal – not yet, anyway – but it’s certainly making falling asleep last longer. And, as it happens, when you’re in your bed, trying to force your brain to shut off, it ends up thinking about more things. One of those things was a memory that earlier this year, I’d read Yuya Sato’s Christmas Terror: Invisible x Inventor. It was translated by Sway Translations (also responsible for translations of some Nisioisin works and – in my mind, most notably – Otaro Maijo’s Disco Wednesdayyy and Tsukumojuuku, two novels which I’ll… eventually talk about here).

As far as I’m aware, the only English-translated book of Sato’s is Dendera, but Danganronpa fans might be familiar with him, as he was the one who wrote the Danganronpa: Togami novels. I myself, though, had first heard of Sato for his 2001 Mephisto Prize-winning entry, Flicker Style. I’ll admit I never read it – primarily because the synopsis didn’t sound particularly appealing.

What ultimately got me to actually read Christmas Terror was the translator’s announcement post on Twitter, pleading for readers and writers alike to read the book. It’s a relatively short work (200-ish pages), so it wasn’t terribly difficult to fulfill the request.

So, I did it!

The story follows a teenage girl, Toko Kobayashi, as she follows an impulse to stow herself away on a cargo ship and finds herself more or less stranded on an island. The island itself isn’t deserted or anything – there’s about 500 people living on it – it’s just that the cargo ship she was on leaves and is scheduled to come back in three weeks’ time. Until then, she stays with a guy called Kumagai, who buys garbage and knick-knacks from the townspeople, packs what he considers usable, and sends it to a wholesale dealer. He has Toko start working for him by packing the garbage for him.

Eventually, however, he gives her a different job – to start monitoring a man living in a little shack. The man’s routine seems fairly straightforward – he appears to spend most of his time alternating between writing on a laptop, eating and sleeping. It’s a fairly monotonous task – until one night, during her watch, the mysterious writer disappears from the shack right under her nose.

As far as the core premise goes, that’s more or less it. There’s other things happening on the island, like a girl who is unable to form new long-term memories. There’s also a second impossible crime that happens fairly late in the story.

From the curt description and the fact it took me months to remember I’d even read the book at all, it’s not difficult to guess I didn’t really gel with it. I don’t even mean that in a necessarily negative way – it’s just this is the kind of work where I feel like, to really connect with, you need to be in a particular mindset and a particular time in your life. There was a point in my life where I would’ve absolutely resonated with what the author is going for here. And while I don’t feel like I’m that person anymore, there was a lot here I certainly recognized from that point in my life.

The first thing I wanted to say is that the plot feels awfully artificial. I feel like, to some extent, that was intentional. It’s almost like a vehicle for the underlying themes of the work – impulsivity, how people view authors, how authors view themselves, memory, even the idea of sorting and recycling of “garbage” – but the actual plot tying them together feels like just that: a plot. If you’re going into this for the locked room – don’t – it’s not that kind of a story. It’s not difficult to figure out as much as you’re reading. There’s a lot of points in the narrative where the narrator seems to pause everything and go off on a seemingly unrelated tangent for a page or two, reinforcing the idea that you’re fundamentally reading a story.

In fact, there’s a sense of anger – I’d even say some low-key hostility towards the reader – as you’re going along, that doesn’t really get to understand until the very end of the story.

I’ve been burying the lede – from this point on, I’ll get right into what the novel actually is and how I personally recognized parts of my past self in it. To some extent, this is probably a spoiler, so if you have any interest in reading it from the (admittedly vague thoughts) up to this point, I suggest you go read it and then come back here after.

Also note that your mileage may vary here. This blog post by Kakuzo offers a more positive outlook on the work and shows a different way of relating to it.

Again – spoilers from this point on.

The work is essentially Sato’s meditation on his career as an author and his own way of saying that he was done. The afterword expresses exhaustion, anger, disappointment and – ultimately – resignation.

There was a point in my life where I looked at the many years I’d been writing and asked myself the question of: “what the fuck am I even doing here?” Objectively speaking, I’m writing in a very particular niche of a genre that could be considered – for all intents and purposes – dead when compared to its glory days. My readership is small, the amount of feedback is even smaller. When you’re going to university or even after, when you’re working a 9 to 5, it’s a reasonable question to ask yourself – “am I spending my time in a reasonable way by doing this?”

What the fuck am I even doing here?

It’s easy to imagine the image of an author that writes for himself – for the very act of writing. But man, it’s fucking hard to be that. The writer that disappears in Christmas Terror actively rejects sharing his work with the outside world and is more than happy to isolate himself – eventually becoming literally invisible to Toko. But in the afterword, Sato himself reflects how he can’t relate to that character. It’s an idealized image – because an author who is content with not putting anything out there is content with nobody seeing it; an author content with nobody seeing it doesn’t need to deal with the awful anxiety of putting effort into creating something and then having few people see it.

Of course, the nuance of this shouldn’t be lost. It’s not that nobody read Sato’s works: it’s that the scope and expectations of the response he wanted (or was expected) to get were so large that, when undelivered, led to hurt.

And look! That’s not unreasonable. It’s not good, but it’s not unfamiliar. The reason I write is for validation, too! I like seeing people reading my work. I like seeing people talk about it. I like seeing people in the community – especially new people – go and say “yeah, I read DWaM’s stuff!” It’s normal! It’s fine! There’s nothing wrong with wanting people to read and like your work!

The issue starts when you trick yourself into thinking that you deserve to be read. That you deserve to be seen. And that, when you aren’t – when you see people talking about things that isn’t your work – you start to turn that irritation on the things they do talk about.

In the mystery story sphere, most of the genre lives on through bloggers talking about the stories. It’s fair to say that a lot of the ones being discussed are Golden Age stories. So then you start blaming the bloggers themselves – you start to perceive them as obsessed with past works and not actively looking towards the future. You develop this narrative that the genre hasn’t made it to the modern day precisely because of people’s obsession with the Golden Age.

It can even mutate. Become more than that. It’s not just a matter of being recognized, it’s about being noteworthy enough to be remembered at all. To leave a mark – to have the thing you made have meaning; and, in turn, to feel like you yourself have some meaning.

Of course, all of that is just bullshit. People do talk about “newer” stuff (Halter, Mead, Byrnside, Carver, Noy, Edwards, Hallett, Innes; even translations of stories never-before seen in English can be considered “new” to the general audience of readers). Why should you be read, anyway? Do they even know you exist?

It’s a trick of the ego – the pain point isn’t “they’re not talking about newer stuff”, it’s “they’re not talking about me”, and let me tell you – that shit can eat you the fuck up. Not just drain you of the motivation to do the work, but change you in a way that you start to think less of the support you’ve been given up to that point. You fall into self-pity. When that doesn’t work, it turns into self-loathing. Nothing ever feels like it’s enough. You always need more. The work starts to become a currency rather than something genuine.

I think, to some extent, it’s why Christmas Terror feels so artificial – because it is. There’s nothing else it can be. The machine has stopped, but the you’re staring at the monitor, an empty doc’s open and a part of you is still demanding to put something on the page.

What else can you do?

You write about the only thing on your mind:

What the fuck am I even doing here?

I’d like to commend the translation team for including an interview with Sato that took place some time after the book’s release. It effectively serves as an epilogue the original story never had, showing that life, in the end, went on. Eventually, he started back up again. He moved past this low point. He managed to struggle back.

You could call it a part of the process. I’d call it a part of growing up. To understand what being an artist actually means to you and reconciling it with what you want it to mean to you.

For me, it was coming to the realization of how selfish and superficial my motives for writing had become. I understood that I had no right to expect to put something out in the world and have everyone just read it – or even know it exists. Getting the word out there was work I thought I didn’t have to put in. Work I didn’t want to put in. (In a lot of ways, I’m still pretty bad at this.)

I learned to reconnect with the actual hobby – the mystery novels that inspired me – and remember that I was allowed to have fun. I re-learned to value the people who had taken the time of their day to read my works and engage with me on them. And while it’s hard to write just for the sake of it, I’d say reigniting that passion brought me a little closer to that ideal.

I’m still shallow, to an extent. I’m still seeking the validation. I still want people to read. But I’m happy for the audience I’ve found. If there’s more, great. If not, it is what it is. Maybe someday a new-modern historian will come across a PDF or two.

Life goes on. Until it doesn’t, might as well write some more.

Translation Links