Beyond Mystery, Beyond Truth

It’s 6 AM. I haven’t slept.

It was 1 AM when I gave up on sleeping. I decided to make myself a cup of coffee. I figured I could read Paul Auster’s Oracle Night. I bought it in paperback when I was at that book fair a few weeks ago. Then I realized the paper didn’t feel good on my fingers and got the e-book. Then I suddenly didn’t feel like reading, so I started watching clips on the Family Guy Funny Moments Twitter account. Then my girlfriend reminded me I should read Scott Pilgrim. So I went ahead and read all of Scott Pilgrim. I liked it a lot.

Now it’s 6 AM. There’s a new cup of coffee on my nightstand.

This doesn’t have anything to do with the book I’m going to talk about. But I think I should mention it in case I stop making sense at any point. In a way, this current, sleep-deprived mindset is the best state I could be in to approach this.

If we’re approaching anything, then it is a hill. And at its base lies Kenji Takemoto’s Paradise Lost Inside a Box.

Japan has what are known as the Three Occult Mystery Novels. The first is Mushitaro Oguri’s Black Death Hall Murder Case – a book notorious for its extreme use of pedantry and near-unreadability (to the point where Japanese people have trouble reading it; seemingly a common problem even in some of Oguri’s preceding works). The second is Kyuusaku Yumeno’s Dogura Magura – which tells the story of its mental patient protagonist through a series of ever-confusing records – this is the one you’re most likely to have heard of, as it does have a movie adaptation and is heavily referenced in the visual novel Hasihime of the Old Book Town. The third is Hideo Nakai’s Offering to Nothingness – known for its over-the-top deduction battles between its amateur detectives.

Of course, I’m keeping these descriptions light because I haven’t actually read any of the three.

Instead, I read the fourth one – Paradise Lost Inside a Box. A masterwork that combines elements of all three of these “anti-mysteries” – the pedantry of Black Death, the story-within-a-story nature of Dogura Magura and the deduction battles of Offering to Nothingness.

The story centers around a group of mystery novel enthusiasts. One of their members, Niles, sets out to write a mystery novel featuring the members.

The first chapter starts with one of the members, Kurano, returning to his house on a hot summer day. He unlocks the front door, sees an unfamiliar pair of boots in the hallway, goes to his room and finds – another member’s corpse there. When he goes back downstairs, the unknown pair of boots has disappeared.

Kurano quickly realizes that the culprit must’ve been in the house and escaped right as Kurano was discovering the corpse. But this, he quickly realizes, is odd – due to the particular way his front door locks, it soon becomes clear that the culprit had gone out of their way to lock themselves in the house along with the victim, meaning that they purposefully left the boots for Kurano to see, and then escaped with them as he was busy finding the body.

Why? This is the driving question behind this mystery.

The second chapter starts with the victim of chapter one reading the first chapter and giving Niles feedback on it. In this chapter, a member of the group disappears from a room – the door of which the rest of the members could clearly see from outside of it.

The third chapter then has a person reading the second chapter and treating it as fiction – but treating chapter one as reality and an actual account of what happened in real life.

In other words, Paradise Lost Inside a Box takes place in two timelines. Both timelines are reading Niles’ work as he finishes things chapter by chapter – the exact same novel you, the reader, are reading. Characters in the odd-numbered chapters treat their chapters as records of what’s actually happened to them, and even-numbered chapters as fiction. And vice-versa – the characters in the even-numbered chapters are written to treat their chapters as records of truth, and the odd-numbered chapters as fiction.

Pretty cool, right?

Each chapter is structured in a similar fashion. A mysterious event happens and the group gathers to discuss it, each member usually providing their own theory on what could’ve happened.

But even here, you’ll find things to be unusual. Obviously, there’s the structure of the novel itself – while each timeline wants to solve its own cases, they sometimes reference the text of the “other side”, occasionally pointing out similarities and differences, and using them to build a part of their solution. This, in itself, should show that these people are a bit unusual – although they do ultimately submit a plausible theory, the way in which they build up to it is often founded in abstract, esoteric or genuine scientific concepts.

For example – in that disappearance in the second chapter, the very first thing one of the characters starts talking about are ideas of matter passing through wall. In another example, character draws a relationship diagram, showing how the members knew of each other beforehand, comparing it to a certain molecular structure, pointing out that it’s not a perfect fit for that structure, but asserting that it must be a perfect fit, and concluding that there must exist unseen relationships between the characters.

And, since they’re mystery freaks, they also build a rule for themselves that their theories should be original and not something previously seen in a mystery novel (an element that, if memory serves correctly now, is a heavy nod to Offering to Nothingness – I think the characters in the story itself might acknowledge it…)

Pretty cool, right?

Well, we certainly aren’t the first to think so.

As I’ve said, we’re climbing a hill here. Paradise is just the base. The road we’re actually taking is through a completely different novel – Kurumi Inui’s Inside a Box.

As the title might suggest, it is heavily inspired by Paradise – a downright pastiche. Both novels are about a group of mystery lovers which start getting plagued by mysterious incidents. Both novels feature a member of a group who is writing a novel that may or may not be reflecting actual events. Both novels are structured in the same way – each chapter contains a mystery event after which the group gathers and discusses potential answers to the mystery. The crimes in both novels are primarily locked room mysteries. Both groups delve into side topics to build their solutions on.

Hell, both novels have Four Scenes in Place of a Prologue and Four Scenes in Place of an Epilogue as the titles of their start and end sections respectively.

The first scene of Paradise is someone wandering the city in a fog. The first scene of Inside a Box is someone wandering the city in twilight.

It wears its inspiration on its sleeve and is proud of it.

It’s worth noting that Inside a Box doesn’t have the dual-timeline structure. Instead, the novel being written takes a backseat this time around – it’s still certainly important, but it’s an element on equal footing with all of the other strange things happening; one of the clues to build deductions on.

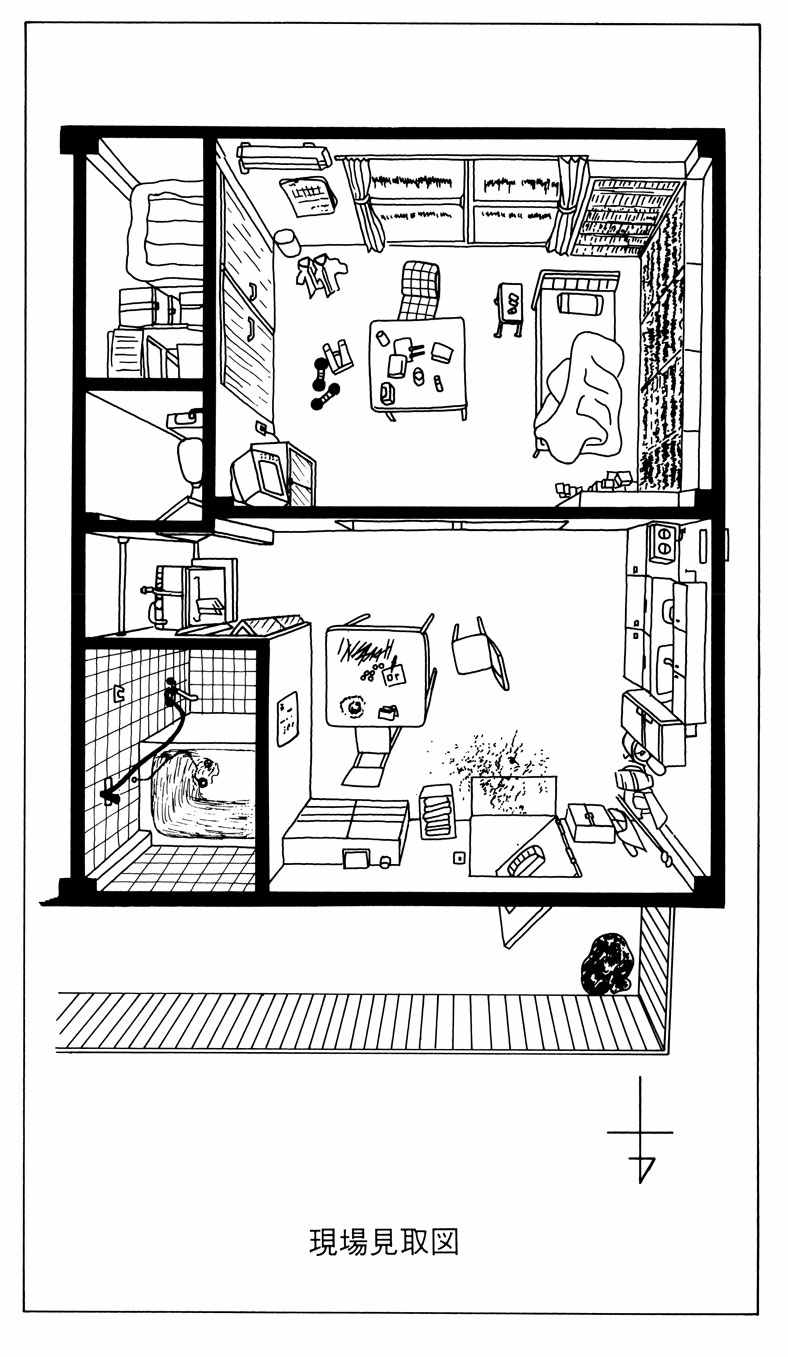

The locked rooms are also their own beast. For example, Inside a Box’s inciting incident is not a murder, but a disappearance: a man steps into his own apartment, slamming the door shut in front of one of the group members’ face. A few moments later, the door is unlocked, and a faint sound of a struggle is heard.

However, when the door is actually opened – the apartment is completely empty.

(The novel also features these pretty illustrations of all of the crime scenes. This, for example, is the apartment in question.)

I read Paradise over half a year ago. Since I’m only now actually writing stuff down, I can only go off my still-lingering memory of it, but I remember liking it.

I read Inside a Box just a few days ago. And I can say with certainty it’s one of my favorite mystery novels of all time.

I cannot tell you that the practical tricks discussed in the book will astonish you. I cannot tell you that the characters are particularly deep (some of them are actually pretty unlikeable, with some relationships depicted pretty uncomfortable by most standards). I cannot tell you that I appreciated all the cluing properly – some of Inside a Box features codes and wordplays which went right over my head. I cannot even tell you that everything is ultimately explained to the satisfaction of your typical mystery novel. A large theme of both of these books are, indeed, the limits of human knowledge and truth itself. In Paradise, each timeline can do no more than believe itself to be reality. In Inside a Box, you will have an explanation for each of the locked rooms – but how much of the bigger picture you’ll understand and, indeed, how much you’ll choose to believe of the provided explanations, will, to some extent, rest with you, Dear Reader.

But what I can tell you that finishing it left me in a certain state which I rarely truly feel with books these days. Not a “damn, now I wanna sit down and really think about what I just read and come up with my own theories” kind of state. No. Just a certain mood. The kind where you feel like you’ve just stepped through the other side of the fog and can see bright city lights. You can hear the noise, but the city feels calm and peaceful and familiar. You’re a little emptier, but you’re not hollow – the incompleteness becoming a comfort in its own right.

Does that make sense? Of course not. The coffee’s cold and I’m barely keeping my eyes open.

But even so, I can still think myself:

“Ah. This is what mystery fiction can be.”

And I fully understand that very few people, if any, will really agree with me on this. I fully understand that people who have read the other occult books will see this one as an inferior imitation of the original or just mediocre. But sometimes you can read a mystery that transcends the expectations of things that are supposed to make mysteries “good”. In the last post, I briefly touched on the importance of questions and answers, and the situations in which one may outweigh the other in terms of a novel’s general enjoyment.

There’s an addendum I’d make to that. Or, rather, a different view on the subject – more in the way I sort of experience mystery novels than a general theory. When it comes to impossible crimes – the main type of mystery novels I read – the most important element is not to the coveted “one true” solution. I don’t need the detective to descend from the heavens and tell me the God-spoken truth. Instead, what I enjoy the most is the way in which the crimes are discussed. I feel like the quality of an impossible crime story is generally tied to the way in which the characters discuss it. I love alternate solutions and I love seeing characters illustrate just how impossible these situations seemingly are through sheer theorizing.

And yet, it can’t be just that, either. For example, half of Death of Jezebel is essentially characters discussing the case and theorizing, and I – personally – don’t adore the book as a lot of other people do, in spite of the solid mystery and solid solution. Because Jezebel doesn’t stop to breathe, and when it does, it’s not long enough. When you’re just constantly (and I truly do mean constantly) attacking the same problem over and over again, there comes a point where you lose that sense of mystique that impossible crimes should carry.

I’ve probably talked about this before, but in the back of my mind, I understand that it’s all possible and reasonable and explainable, but there should be a part of me that lives in fear of otherwise. But every time Inspector Charlesworth’s theory is denied, he just picks himself back up and immediately tries again. It erodes that special something – that secret sauce that truly makes impossible crimes so unique in the larger genre.

This is the top of the hill, and I guess I’m dying on it.

One way to temper the “issue” I feel with Jezebel would be to properly pace out the theorizing sequences. But in Paradise and Inside the Box, we go a step further – the characters walk through the mystique – through the weird logic, through the esoteric interpretations, through scientific concepts – to get to their own unique truth. That’s probably why the novels appeal to me as much as they do. You see a reasonable explanation for all the facts, but you also see something more – it’s just in the corner of your eye – it’s all of that strange stuff they’ve been saying lingering just out the corner of your eye, and you wonder if there’s something more. Something that, when you see – when it truly – comes together, is, for lack of no other word – genuinely beautiful.

The Epilogue of Inside a Box is beautiful.

And, y’know, I might be the only one to feel that way. I might be over-exaggerating. If you give me a few weeks, I might very well forget this feeling; maybe even forget the book altogether. Or, worse yet, let it sit for long enough to realize the things I appreciated about it weren’t that special at all, and that, as I’m writing this, whatever thesis I’ve presented has about a million counter-examples.

But that’s fine. At this point in time, as I write this, the feeling of the Box still lingers, and it’s a very cool feeling, and I feel like it’s important to leave a trace that it was, in fact, there.

So, here it is.

The box. The paradise.

Product Links (Amazon)

Other Links